Copper Cactus. Steampunk Stick. Slim Jim.

Whatever you call it, the J-pole antenna is a reliable alternative to verticals and ground planes for VHF/UHF communication. Due to their simple construction, J-poles are generally inexpensive and easy to build with readily available materials. You can design one to be relatively compact—great for situations where space is limited or to placate HOAs.

One of the main advantages of the J-pole antenna is that it doesn’t require radials or a ground plane. This makes it easier to mount on a roof or pole. The use of no radials also reduces wind resistance, simplifying overall construction and providing a more convenient solution for many radio applications.

The J-pole feedpoint is at DC ground, so it has a low noise floor and does an excellent job of receiving signals. There are several variants. The Slim Jim is an end-fed folded dipole antenna. The Super-J antenna has an added half-wave element, and the Collinear-J antenna adds a phasing coil to the Super-J.

J-Pole Antenna History

The J-pole, also known as the J antenna, is a vertical omnidirectional antenna initially used in the shortwave frequency bands. It was invented by Hans Beggerow in 1909 for use with Zeppelin airships, hence the nickname Zepp antenna. The J-pole was comprised of a single-element, one-half-wavelength long radiator with a quarter-wave parallel tuning stub. The long, weighted antenna wire was reeled out from the rear of the gondola.

The purpose of Beggerow’s invention was to move the antenna’s high-voltage points away from an airship’s envelope to reduce the risk of igniting the ever-present hydrogen leaks. The feedpoint and a counterpoise for the antenna wire were attached to the gondola.

By 1936, the original Zeppelin led to the J configuration, now known as a J-pole. This version was used for land-based transmitters, with the radiating element and the matching section mounted vertically and forming an approximation of the letter J. When the radiating half-wave section is mounted horizontally at right angles to the quarter-wave matching stub, the variation is also classified as a Zepp antenna.

How the J-Pole Works

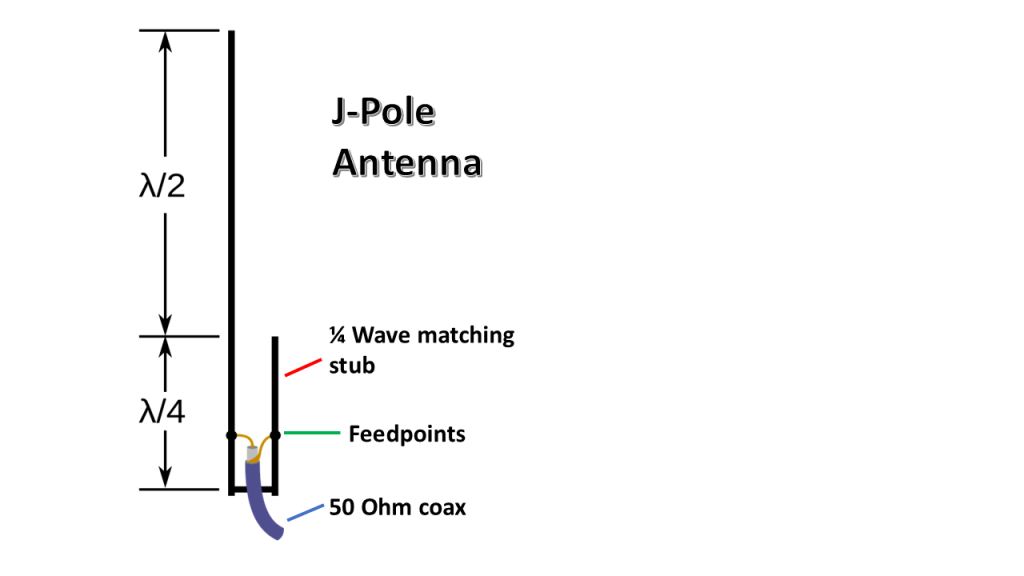

The basic J-pole antenna is a half-wave vertical radiator, much like a dipole. What makes it different is the method of feeding the half-wave element. A conventional dipole is fed in the middle, creating two quarter-wave elements. The J-pole is fed at the end of a half-wave radiator.

A half-wave antenna fed at one end has a current node at its feedpoint, giving it a very high input impedance near 2,400 ohms. This is much higher than the impedance of commonly used 50-ohm coaxial cable, requiring an impedance matching circuit between the antenna and the feedline.

Instead of using a transformer or balun, the antenna is matched to the feedline by a quarter-wave transmission line stub shorted at one end and connected to the half-wave radiator’s high impedance at its other end. Between the shorted and high impedance ends there is a point that is close to 50 ohms. This is where the feedline is attached. Because this is a half-wave antenna, it will exhibit a gain of nearly 1 dB over a quarter-wave ground-plane antenna.

J-pole antennas are somewhat sensitive to surrounding metal objects and should have at least a quarter wavelength of free space around them. There is some disagreement whether there should be any electrical bonding between antenna conductors and the mounting pole or tower to ground. Some do so to keep static charges from building up or for lightning protection. No ground is required because the J-pole is 1/2 wave or longer. The best advice would be to try it and see if the matching is significantly affected.

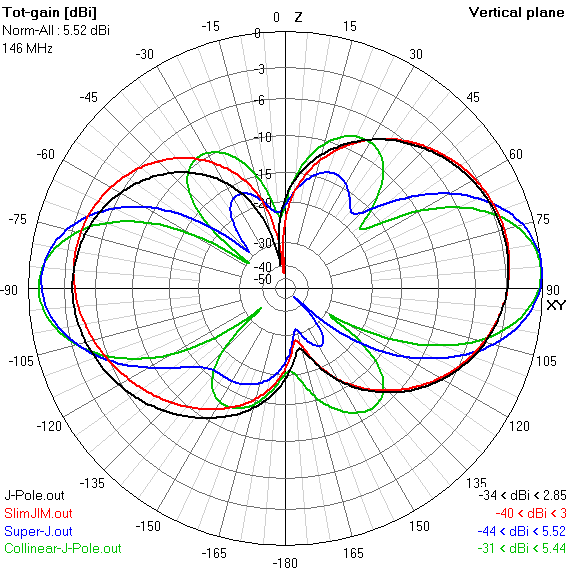

Primarily a dipole, the J-pole antenna exhibits a mostly omnidirectional pattern in the horizontal plane with an average free-space gain near 2.2 dBi (0.1 dBd) over the standard dipole. The quarter-wave stub modifies the circular pattern shape, increasing the gain slightly on the side of the J stub element and reducing the gain slightly opposite the J stub element.

The J-pole has a mostly omnidirectional radiation pattern in the horizontal plane, meaning it transmits and receives signals in all directions around the antenna. A J-pole antenna typically has a slightly elevated takeoff angle, with the exact angle within a range of 10 to 20 degrees from the horizontal plane. The exact takeoff angle can be influenced by how the J-pole antenna is mounted, including its height above the ground.

J-poles are not limited to the VHF and UHF bands. They can also be utilized for HF but, for practical reasons, you probably won’t see many built for bands below 10 meters. To put things in perspective, a 10-meter J-pole would have a long element of 24 feet (tall, but manageable). For 20 meters, we’re near 50 feet in height. That’s a lot of copper or aluminum.

J- Pole Variations

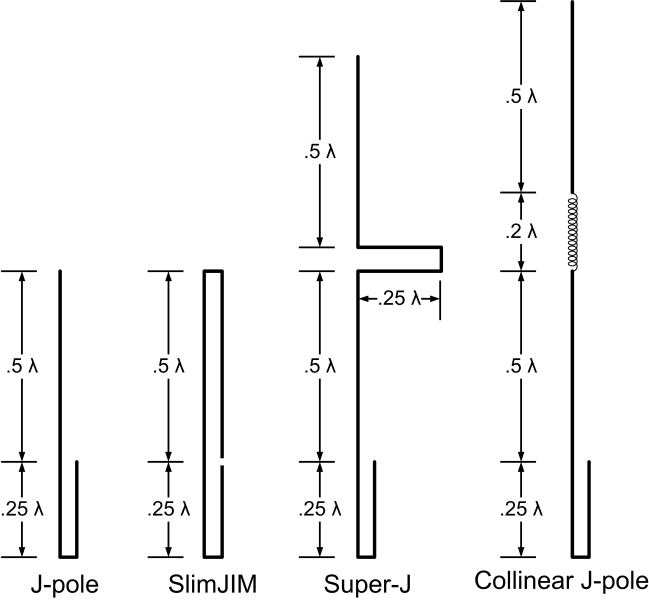

The J-pole has been the focus of more than its share of tinkering. Here are some of the more popular variations, with the original J-pole pictured for comparison.

- Slim Jim: Fred Judd, G2BCX, introduced his J-pole variant in 1978. The Slim Jim name comes from its profile and the J-type matching stub (J Integrated Matching). It performs similarly to a folded half-wave antenna and is virtually identical to the traditional J-pole construction.

- Super-J: This version of the J-pole antenna adds another collinear half-wave radiator above the conventional J and connects the two with a phase stub to ensure both vertical half-wave sections radiate in current phase. It has more gain than a conventional J-pole, but less than a collinear.

- Collinear J-Pole: This J-pole uses a phasing coil with a physical length of 0.2 wavelength. A phasing section is required between two elements of the antenna for them to radiate in phase. In fact, the phasing coil is part of all collinear antennas. Gain is about 3 dB over a conventional J-pole.

Given that small changes can make these variations more or less effective, don’t take the gain figures too seriously. Relatively speaking, the basic J-pole and Slim Jim have a slight advantage over a dipole’s 2.15 dBi isotropic numbers, followed by the Super-J and Collinear in that order.

DIY J-Pole

Want to build one? You’ve got several options when it comes to design and materials. The classic copper J-pole is made from copper tubing and fittings, which you can find at big box stores or your local hardware shop. You could also use aluminum tubing, which is available from DX Engineering.

Copper J-poles require some basic soldering skills with a propane torch. There are dozens of YouTube videos explaining the build process, as well as articles and plans explaining the parts, measurements, and tuning procedures to get the lowest SWR readings. Use your favorite browser to locate plans for the J-pole variation you’d like to build for your station.

Another option would be to use PVC pipe as a housing for the twin-lead J-pole antenna discussed in the next section. ABS and Schedule 20 PVC pipe are recommended choices and can be found at most big box and hardware stores. Typically, 1/2 and 3/4 inch pipe is used depending on the width of the twin-lead/ladder line.

Whether twin-lead or tubing, you should add a few snap-on ferrites on the coax near the antenna feed to mitigate common-mode currents.

Antenna Roll-Ups

If you’re not into plumbing or metal work, there’s an inexpensive option that’s relatively easy to build and versatile. A twin-lead J-pole antenna is a good addition to your emergency go-kit. When rolled up, it is a highly compact antenna you can stash in your pocket. It’s effective and provides about 3 dBi of gain with a low takeoff angle. When used on your HT, it will dramatically outperform your rubber duck.

Hang it on a tree or tape it to a wall or window. It makes a great portable antenna for hotel rooms, vacation homes, or emergency ops. You’ll squeeze every ounce of performance possible out of a 2-meter HT. Being a half-wave antenna, it is not dependent on a ground or radials for proper performance. If you don’t mind the extra length, it makes sense to ditch the rubber duck.

Not a maker? Ready-made J-poles can be found at DX Engineering and online.

How Does It Stack Up?

Like most antennas, you’ll find those who will swear by them—or swear at them. As an alternative to other commercially available 2M/70cm antennas of various designs, they are a cheap and relatively easy-to-build DIY project. Off-the-shelf J-poles have the benefit of the developer who figured out the needed fixes and quirks to be addressed.

L. B. Cebik, W4RNL (SK), noted that “A J-pole is an imperfect antenna that happens to do a very good job as a practical antenna. It has served well for many decades as an omnidirectional vertical antenna that most users can build from materials available in the home shop or garage, or from materials available at the local hardware depot.”

The J-pole is a forgiving antenna and somewhat practical on the 10- and 6-meter bands. However, measurements and tuning become more critical on 2 meters and up, so using an antenna analyzer is highly recommended for making adjustments.

The Good

- J-poles have more gain than a quarter-wave ground-plane antenna.

- J-poles have a lower angle of radiation than the dipole—good for 2M/70cm.

- Copper J-poles are known for their durability.

- J-poles don’t require counterpoise/radials.

The Not-So-Good

- Nearby large metal objects can detune a J-pole. You should keep them at least six feet away.

- They’re known for producing common-mode current.

- J-poles can be difficult to tune, especially on UHF bands.