As a newly licensed ham, you probably got started in amateur radio with VHF and UHF phone operation. A simple click gave you access to FM simplex channels and repeaters stored in memory—so easy a caveman could do it. No fine-tuning was necessary in the channelized world of VHF/UHF FM.

But when you moved to the world of single sideband (SSB) phone operations, it was a whole different story. Changing frequencies required a new skill set to carefully tune in those weird sounds that reminded you of Donald Duck squawking in an unintelligible dialect. Also, you needed to match the frequency of the station calling CQ so they could copy you. Remember, by default, your radio transmits and receives on the same frequency.

Close isn’t close enough.

Practice helps, and most radios have receiver/transmitter incremental tuning (RIT/XIT) features to help keep you on frequency and hear those who aren’t.

What Does RIT Mean?

RIT on a receiver stands for “Receiver Incremental Tuning,” a control that allows you to slightly adjust the receiver frequency without changing the transmitter frequency. You fine-tune the incoming signal to improve clarity and reception quality without asking the other station to adjust their radio. For example, when you’re talking to a group—like in a net—you can fine-tune the ham who’s off-frequency while everybody else in the group hears you without detecting any change in your frequency.

Many CW operators prefer to use RIT to tune the receiver slightly higher or lower than the zero-beat frequency, changing the demodulated tone of the received station without changing the transmit frequency. If you prefer to change the zero-beat tone you receive, use the RIT function so that both your station and the contact station can maintain the zero-beat transmit frequency, keeping bandwidth to a minimum.

What Does XIT Mean?

XIT, “Transmit Incremental Tuning,” performs the reverse function. It keeps your receive frequency constant while you adjust your transmit frequency. Tuning with the big VFO knob will adjust both the transmit and receive frequencies simultaneously, while tuning with RIT or XIT will adjust only one of them.

Yaesu calls RIT/XIT clarifier on their radios. It enhances the received signal by fine-tuning it to compensate for slight discrepancies between the transmitting and receiving stations. Icom uses ΔTX to represent the XIT function on the front panel.

Doing a Split

The RIT/XIT feature can also help you operate in split mode. So when do you use it?

If there’s a rare DX station calling CQ, you’ll likely find a pileup—way too many stations fighting to make contact. To help control the chaos, DX stations often transmit on one frequency and ask stations to call on another. This is called operating split.

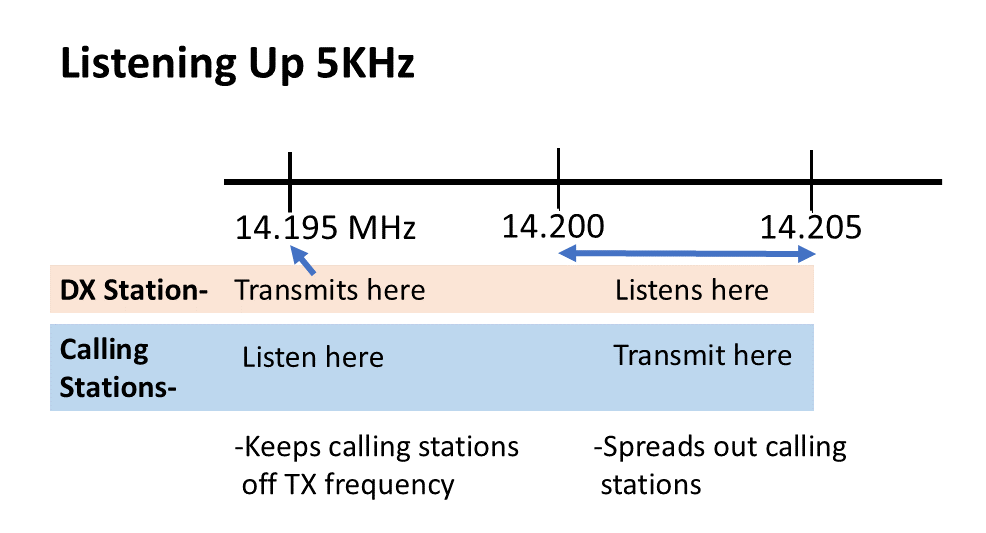

The DX station will say something like “Listening UP 5,” meaning stations should move up 5 kHz from this frequency to make calls. It clears the original calling frequency for the DX station and hopefully relocates the stations seeking a QSO. Of course, there will be some people who didn’t hear or ignore the instructions, and you’ll often hear a chorus of “UP 5, UP 5″ from other stations as a reminder.

For most of us, we are on the opposite side of this pileup. This is where XIT is useful. Set your VFO to the DX station’s transmit frequency and tune XIT up 5 kHz or so. Usually, you’ll find stations lurking slightly above or below 5 kHz. While the DX station is running through a bunch of people calling, we can periodically listen in on our transmit frequency (XFC button on Icom radios located beside the VFO knob) to determine the frequency of the station currently being worked.

We listen to the DX station and as soon as the current contact is completed, we know where the last contact was transmitting and immediately call on the same frequency. This can greatly improve our chances of being heard by the DX. We can also listen to several consecutive contacts and find a pattern of how the DX is listening—for example, slowly working stations on higher and higher offsets, returning to UP 5, and repeating. Figuring out patterns in a pileup will improve your chances of breaking through.

Modern radios that have RIT and XIT typically also have a button you can use to listen on your transmit frequency. This means that if you use RIT, you can listen on your transmit frequency (rather than on your receive frequency). On the Icom, it’s the XFC located beside the VFO knob.

There are limitations using RIT/XIT. Modern radios like the Icom IC-7300, Yaesu FTDX10, and Kenwood TS-590SG can adjust RIT/XIT up to +/-10 kHz. Older radios may have a smaller adjustment range. For example, the Kenwood TS-830s, a tube/transistor hybrid radio, maxes out at +/- 2 kHz. If the DX station announces “listening 15 UP,” you’ll need to use a different solution.

Other Split Options

Another alternative can be used with radios that have two VFOs, A and B. It’s similar to RIT/XIT but lets you select the transmit VFO (press A/B to choose) to set your transmit frequency. Then, press A/B to select the receive VFO to set the operating frequency and push the SPLIT button. When you transmit, the transceiver will automatically switch VFOs for you and switch back for receive. You should see the frequency change when you transmit, then return to the receive frequency when you finish.

Consult your radio manual for specifics on VFO A/B functions.

Also, check out the OnAllBands article, “Your First Pileup: Techniques for Success” for additional information about utilizing dual receive.