Most days, the CW bands are kind of quiet. But on certain days, suddenly there are stations tuning up, conducting short QSOs, and then at the top of an hour – WHAMMO – there are CW stations all over the place, going lickety-split! Sure sounds like they are having a good time, so what does it take to merge into that traffic? This article will give you some ideas and explain the basics, starting with readers who are eager to learn CW. If you operate some CW already and want to give contesting a try, we’ll talk about getting your station set up and provide some beginner-friendly strategies.

Just Getting Started?

If you are just getting started with CW, there are a number of online groups that will help you. For example, the FISTS society has a chapter on every continent, practice programs, and will even pair you up with a “code buddy” for on-the-air practice. The Straight Key Century Club (SKCC) is another good group.

If you are currently using a straight key to send CW, you can probably push yourself into the 20 WPM range, but it’s a lot easier to use a paddle and a keyer as soon as you are comfortable with the basics. That lets you keep increasing your code speed without having to change from a straight key and learn a new way of sending just as you’re getting good at it! You can borrow a paddle and keyer to get going and buy your own after you decide what you like.

Getting Hooked Up

Once you’re comfortable with CW, you’ll want to be sure your station is set up properly. I assume that you have a paddle, a keyer, and a PC (laptop or desktop) that you can use to log your contacts and send CW messages. Practice using semi- or full break-in mode (see your radio’s user manual) to become comfortable with hearing what’s going on in between the code dits and dahs.

Most modern transceivers have a CW keyer built in and you can plug a paddle right into the radio. This is fine if you plan on sending everything by hand. That’s usually the first step as you get used to how it all works. You’ll find this gets old quickly, so plan to use your PC to send the most common messages: CQ, your call sign, and the contest exchange. A general-purpose logging program might have a contest mode, or you could try a contest logging program like the basic N3FJP programs or the more advanced Writelog or N1MM+. Software will make your contest experience a lot easier.

While some logging software supports connecting a paddle to the PC, it’s easier and more flexible to combine the PC with an external keyer because the controls for speed and message record/playback are easily available. When using a keyer, you should connect it to the radio’s straight key input so that it doesn’t try to convert the keying signal to a stream of dots or dashes. (The radio may have separate paddle and straight key jacks, or you may need to configure the keying input for a paddle or straight key.)

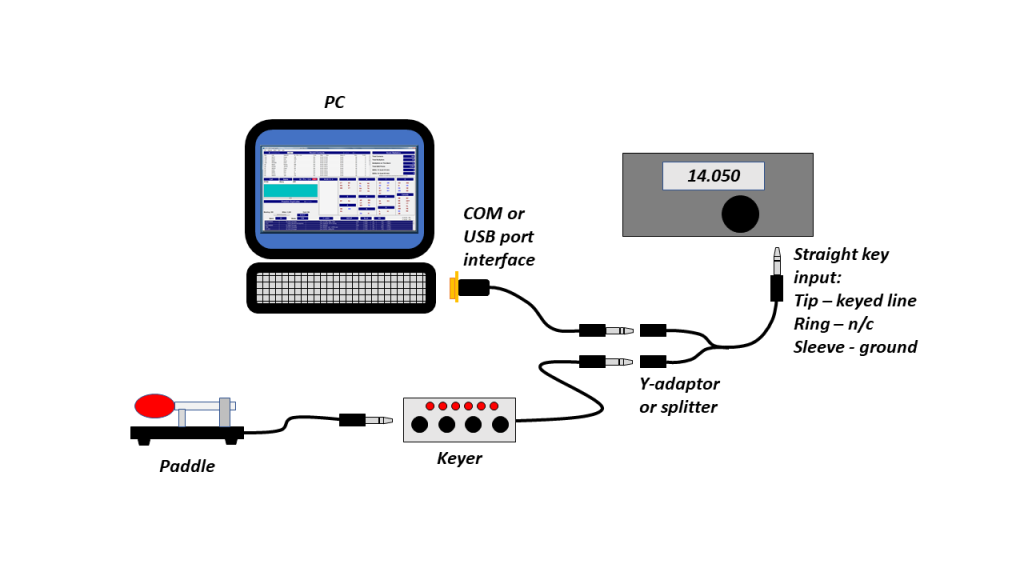

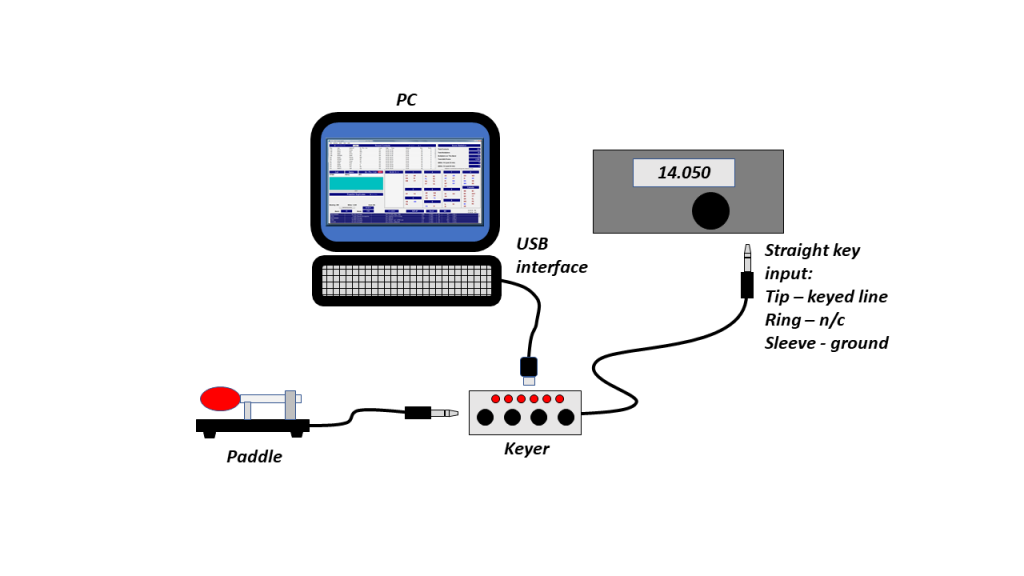

The two most common ways of connecting a keyer and a PC together for CW contesting are shown in Figures 1 and 2. In Figure 1 above, the PC uses a COM port or USB CW interface with a keying output that acts like a straight key to your radio. The paddle connects to the keyer which also has a keying output. By connecting both keying outputs together with a Y-adaptor or splitter, either can key the radio. N3FJP has also published schematics for building your own COM or LPT port CW interface.

Learning and Practicing the Exchange

You have the PC and your keyer connected to the radio and everything sounds good. What’s the next step? I will be the first to agree with you that the code speeds in big contests are VERY intimidating! But take heart. You don’t have to be that fast yourself and there are lots of contests with more relaxed rates. If you can send and receive in the range of 15 to 20 WPM, you are ready to give it a try.

Finding a CW contest is not hard—there are a few every weekend, some big and some little. You can use the WA7BNM Contest Calendar (click on “CW Calendar”) to find suitable contests. Start with a state QSO party or similar smaller contest at first. Both FISTS and SKCC sponsor on-the-air slow-speed events and short contests just for beginners, and don’t forget the ARRL’s CW edition of the Rookie Roundup in December.

Read the rules to learn the contest exchange. What you’re looking for is a contest with a simple exchange that is the same for every QSO. For example, the North American QSO Party contest exchange is just your name and state, province, or country. The consistent exchange makes it easier for you to be sure of the other station’s information before calling them.

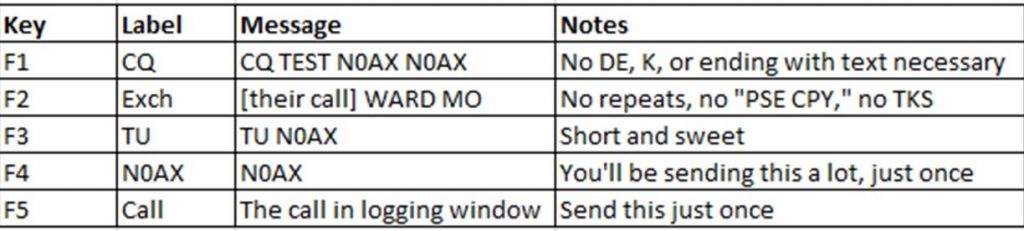

Next, program your keyer or contest logging software with the most common messages. There isn’t a standard message order, but this list is pretty common and how I would program my messages on a PC:

A typical contest QSO might sound like:

W1AW: CQ CQ W1AW W1AW

N0AX: N0AX

W1AW: N0AX HIRAM CT

N0AX: W1AW WARD MO

W1AW: TU W1AW

That’s it—don’t add extra characters to the message or your call sign, like /QRP. Keep it very efficient and direct.

Configuring Your Receiver

The most important settings in CW contesting are in your receiver. Unless absolutely necessary, turn off the Preamp, the Noise Blanker, and the Noise Reduction features. All of those can create distortion from overload or by audio processing. If the band sounds noisy, turn down the RF Gain control until you can still hear stations comfortably with a minimum of background noise.

Your receiving filter should be set to or selected for a 400 to 600 Hz bandwidth, approximately centered on a pitch that is comfortable to your ear. Wider filters will let you hear other stations and narrower filters may produce a difficult-to-copy tone. Be sure Receive Incremental Tuning (RIT) and any kind of passband shift are off so you won’t be off-frequency. Set your tuning step size so that one turn of the main tuning knob changes frequency by about 1 kHz. You’ll find the most comfortable setting as you get more experience.

Next week we’ll explore tips on practicing CW contesting and making QSOs for real.