In the course of my ham operations, I sometimes hear stations that splatter, some more than others. Last week, there were a couple of DX stations that obviously wanted to be heard. The audio was over processed and their amplifiers were being pushed to the limits. What surprised me was when the operators identified their station equipment, it was generally of good quality—something you’d think would sound better.

Splatter on SSB transmissions, by definition, is high-order intermodulation distortion (IMD) caused by overdriving on speech peaks, and it’s totally avoidable. It’s likely these ops have fallen victim to AKTC Syndrome (All Knobs Turned Clockwise), a method where operators simply turn all the knobs on the transmitter fully clockwise for maximum loudness. This keeps the adjustments simple, but they’ll never sound very good on the air—just loud.

Some digital operators also like to crank the audio, believing it improves their reach. The eSSB (Extended SSB) aficionados are interested in exploring the ham version of hi-fi above a 3kHz bandwidth. Both can become an issue on crowded bands or around weak signals.

Modern transmitters are clean when properly operated according to instructions. It often takes deliberate efforts to make them cause problems, and there are some individuals who insist on doing so, regardless of how it affects others on the air. On the flip side, there are hams who take pride in producing pleasing audio using only the bandwidth actually needed.

Keeping it Clean

FCC Pt. 97 Regulations outline the rules regarding bandwidth and splatter.

§ 97.307 Emission Standards

(a) No amateur station transmission shall occupy more bandwidth than necessary for the information rate and emission type being transmitted, in accordance with good amateur practice.

(b) Emissions resulting from modulation must be confined to the band or segment available to the control operator. Emissions outside the necessary bandwidth must not cause splatter or keyclick interference to operations on adjacent frequencies.

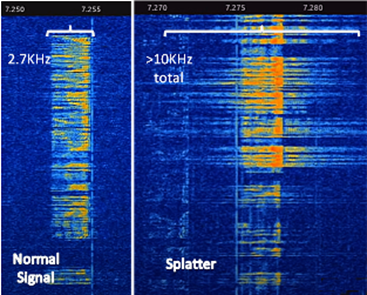

How can you keep your rig audio sounding good while keeping the bandwidth/splatter under control? Let’s compare a normal SSB signal and one with splatter side-by-side.

On the left side is a normal LSB signal, about 2.7kHz wide without splatter. On the right, you can see a similar signal with splatter, occupying a bit more than 10KHz total—limiting effective communications for others on either side of the main frequency.

There are several controls available on your transceiver that can limit splatter. You can produce a clean signal without generating audio harmonics that distort it to the point of unintelligibility or having them appear outside the desired maximum bandwidth of 3kHz. All of the examples below are based on the Icom IC-7300 HF Plus 50 MHz Transceiver, so be sure to check the instructions for your specific rig. The procedures are usually very similar.

ALC, Microphone/Audio Gain

ALC (Automatic Level Control) is a circuit which can be used to form a feedback loop between the transceiver’s audio level and its power amplifier. When improperly adjusted, the ALC can cause severe distortion and a lot of signal splattering. Note that ALC is actually a voltage level in the radio that helps balance the output, not an actual knob or button.

When in SSB mode, touch the TX meter until the ALC scale appears, press the MULTI button, then select MIC GAIN. Transmit, holding the mic between 2 and 4 inches from your mouth. Speak in a normal voice and adjust your mic gain so that the ALC indicator registers somewhere between 30-50% of ALC scale on voice peaks.

Digital signal bandwidth is 50Hz for FT8, so make sure to adjust your PC sound card’s audio drive as necessary while watching the ALC level. Peaks should be near the lower end of the scale. Too much drive will cause splatter that can obliterate nearby signals in an already crowded slice of the band.

If ALC levels change significantly when moving to other bands, check your antenna SWR. It could be a result of the ALC reducing the transmitter’s power output due to higher SWR levels.

Compression/Speech Processor

These terms are often used interchangeably on ham transceivers. Compressors are usually described as giving your signal more punch or talk power. Under normal conditions, properly adjusted audio provides a duty cycle of 20% (20W average power). With compression, output can be increased up to 40% (40W average power.) If you adjust your speech processor correctly, you can have a relatively clean signal with more punch that snags the DX and doesn’t offend local stations.

Icom recommends that the ALC be set first (see previous step.) Touch the multi-function TX meter on the 7300 to display the COMP meter. Push the FUNCTION button located below the display, which opens the FUNCTION screen. Press MENU, then AUDIO. This will give you a larger COMP meter and allow you to see a graphic rendering of your audio. Press the MULTI button, then COMP to adjust the compressor settings.

While speaking into the microphone at your normal voice level, adjust the speech compressor level to where the COMP meter reads within the COMP zone (10 to 20 dB range). If the COMP meter peaks exceed the COMP zone, your transmitted voice may be distorted.

When in doubt or if problems arise, back off the compression or switch it off. A loud signal isn’t any advantage if no one can understand you due to a distorted signal.

Microphone EQ

One of the easiest methods to increase intelligibility is to simply drop some of the bass response and increase the higher frequencies in our voice signals, giving an increase in perceived SSB power at the receiving end. Minimize any part of the audio signal below about 300Hz, and don’t waste bandwidth transmitting sound above 3kHz. The real information-carrying part of speech lies between 300 to 1,500Hz.

To access the screen on the 7300 to adjust bandwidth, press MENU, SET, TONE CONTROL, TX, SSB, and find the TBW settings. Set the transmission passband width of wide, mid, or narrow by changing the lower and higher cutoff frequencies.

• Lower frequency: 100, 200, 300 and 500 Hz

• Higher frequency: 2,500, 2,700, 2,800 and 2,900 Hz

In this menu you can also boost or cut transmit bass and treble in steps ranging from -5 to +5. This is a rough, rather than fine, adjustment on the 7300, and you’ll need to tweak using on-the-air reports. Other transceivers have more exact adjustments that can be made by audio frequency ranges.

Other Considerations

Be sure your power supply output is at 13.8-14 VDC. IMD generally improves when supply voltage is higher. 13.8V is noticeably better than 12.0V.

The best IMD numbers happen when there’s a 50-ohm load. Consider using a tuner, even with an acceptable SWR of 1.5:1 or 2:1. Monoband antennas can also help you attain close to a 50-ohm load, with the added benefit of reducing harmonics.

There has been a lot of discussion whether to use the amp-to-transceiver ALC connection. External ALC is not universally recommended by RF amplifier engineers as an effective way to protect the RF input stage of an amplifier. It was intended for gross overdrive protection only.

Most of the high-end amplifiers manufactured today, especially solid-state amplifiers, contain ALC and protection circuitry to prevent high RF exciter drive levels from damaging them. Many of the older tube-type amplifiers can easily tolerate 100 watts of RF input, the maximum output of most transceivers.

Takeaways on Reducing Splatter

- The ALC meter is an important tool for finding the best mic gain level. Check the radio’s operating manual for recommendations.

- Experts advise keeping ALC activity low—set the mic gain so the meter just shows ALC activity on your voice peaks (30-50% on the IC-7300).

- Collect on-air signal reports in a variety of band conditions to check your audio. It also pays to listen on a second receiver using headphones if you can. Your transceiver monitor may not always give you an accurate sampling of your transmit audio.

- More isn’t always better. Resist the urge to crank up the mic gain and compressor to their maximum settings, likely turning your audio to mush.

- Your ultimate goal is to have a signal that’s clean, punchy and doesn’t splatter.