All things being equal…

Here comes fall, the time of year when the northern hemisphere emerges from the summertime HF doldrums. At the same time, the southern hemisphere hams are finishing their winter and looking forward to spring on the HF bands. Right in the middle of this transition is September’s autumnal equinox (the opposite occurs at the vernal equinox in March).

What is special about this time of year on the HF bands? Let’s back up a bit. If you have been active during the summer, you know that daytime propagation on the higher HF bands (20 through 10 meters)—pretty good up through late spring—took a dive through the day. Why does it do that? Isn’t the northern hemisphere tipped toward the Sun in the summer? Shouldn’t that pep up the F regions for better long-distance skip?

While it’s true the northern ionosphere gets more solar ultraviolet (UV) during the summer days that increases ionization in the F region, extra UV also increases absorption in the lower D region. A signal making multiple hops just doesn’t get through! Summertime sporadic E (Es) propagation on 15, 12, and 10 meters helps keep things busy with “short skip” to stations 1,200 to 1,500 miles away.

Propagation on the lower bands (30 through 160 meters) in the summer suffers as well from the higher atmospheric noise levels caused by stormy weather. Meanwhile, our friends in the southern hemisphere are enjoying great wintertime conditions on the low bands. If you can hear them through the QRN (static), summer can be a productive season for low-band DXing.

As we approach either the fall or spring equinox, sunlight begins to illuminate both north and south equally. Right at the equinox, the terminator between day and night is aligned exactly with the North and South Poles. Equal amounts of solar UV hitting the ionosphere means paths between the north and south hemispheres will open earlier and stay open longer. This gives stations in both hemispheres better chances for really long-distance F region propagation on the high bands. Thunderstorm season has passed, so the low bands are much more hospitable to DX contacts with stations exiting the summer months as well.

Let’s take a look at some examples from the online propagation prediction website, VOACAP. The following maps were generated for current levels of sunspot activity (SSN = 16) and 20 meter dipoles were specified for both transmitting and receiving, one wavelength high for good low-angle performance. CW at 100 watts was the selected mode as a compromise between FT8 (higher signal-to-noise ratios or SNR) and SSB (lower SNR).

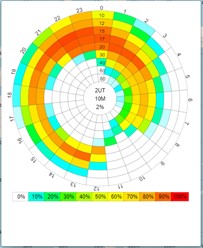

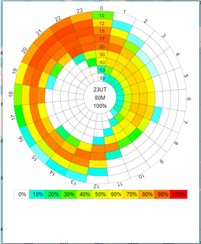

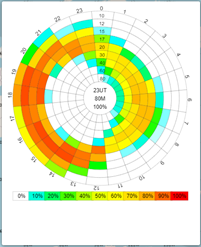

I used the “Prop Wheel” function to generate predictions for all of the HF bands between Buffalo, NY, and Santiago, Chile. This path between two populated areas is almost directly north-south. One set of predictions was generated at the summer solstice in June, another at the vernal equinox in September, and one more at the winter solstice in December.

The Prop Wheel colors show the probability of a band from 80 through 10 meters being open during each clock hour from 0000 to 2300 UTC. A color scale is below each chart. If you want to know what’s happening on a particular path, this is a great way to summarize the predicted behavior!

June – Summer Solstice

September – Vernal Equinox

December – Winter Solstice

Under the summer solstice’s maximum sunlight, propagation favors 15, 17, and 20 meters in the late afternoon and evening. During these hours, the Sun is no longer shining directly on the path, but there is still enough ionization in the F region to support the two long hops required between these two locations. The path is mostly closed between 0800 UTC and sunrise because the southern ionosphere doesn’t get as much UV as in the north.

As the season changes to the September equinox, you can see the opening shift earlier in the day—not so much absorption—and it extends to the higher bands. 10 and 12 meters are great bands on a north-south path in the fall, and 15 meters is reliably open for 13 hours—all day! After dark, 20, 30, and 40 meters pick up the slack. There is probably going to be usable propagation on this path 24 hours a day on one band or another.

Finally, at the winter solstice in December, the strongest openings are in the morning until mid-afternoon, more closely aligned with UV radiation of the F region. 17 meters and 20 meters are doing most of the work through the day. The low bands are open more through the night on this path, although it is the southern hams who have to fight through the QRN to hear us in the north.

You don’t have to analyze each path to get a general sense of what propagation is up to as the seasons change. Guided by The Shortwave Propagation Handbook propagation predictions for low-sunspot conditions, here’s a summary of HF propagation at the equinox:

10, 12, 15 meters: Openings will be most frequent and strongest on 15 meters. 12 and then 10 meters will have short openings, mostly on north-south paths. Watch for signals from African and Australian stations after their sunrise.

17 and 20 meters: 20 meters really shines around the equinox and will feature openings to just about anywhere at some point throughout the day. 17 meters frequently opens as well during 20 meter propagation. Watch for gray-line propagation around sunrise and sunset.

30 and 40 meters: These bands will open to the east as sunset approaches and then stay open all night. Propagation will change to favor north-south paths through the night and then toward the west as sunrise approaches.

80 and 160 meters: Take advantage of the lower noise levels on both ends of the north-south paths. Watch for the best openings at local midnight and again near sunrise on either end of the path.

On all of the bands, try to be active around sunrise and sunset as the terminator approaches and then passes your location. Because it goes directly over the poles at the equinox, it is also close to the most distant locations from your station. Whatever gray-line enhancements exist, around the equinox is when they are most likely to occur. Don’t hesitate to call CQ, as well, no matter what mode you use. You may be pleasantly surprised by a faraway DX station’s answer!

There is one “gotcha” to the equinox, and that is the increased level of geomagnetic storminess around the equinox. This occurs because the Earth’s geomagnetic field, or GMF, is better aligned to interact with the interplanetary magnetic field, or IMF. Aligning the fields enables charged particles from the Sun to enter the Earth’s atmosphere and create a disturbance. The charged particles can come from a coronal mass ejection (CME) or from the solar wind.

The equinox is a good time to watch websites like NOAA’s Spaceweather Prediction Center or SolarHam by VE3EN for warnings of possible geomagnetic storms or other types of active conditions that affect HF propagation. Of course, these storms aren’t all bad news — tune on up to the VHF and UHF bands for enhanced propagation when they occur!

There is so much to learn about propagation, isn’t there? The ARRL’s Antenna Book has an extensive Propagation chapter. In QST and CQ you will find columns and articles on propagation. The ARRL’s weekly Propagation Bulletins by K7RA are a great way to keep up to date, and so is W3UR’s Daily DX, which features regular propagation updates by W3LPL.

This is a great illustration of what I mean when I explain to non-hams that “I can hear the world turning!” on the HF shortwave bands. Different bands open and close all day as the path is in daylight and then darkness. Throughout the year, those same bands have different characteristics that change with the seasons. And finally, the Sun is turning and churning too, and as more sunspots emerge in Cycle 25, these charts will look a lot different! Every path has its own characteristics, and then there are the differences between short- and long-path propagation. It can keep a ham busy since there is always something new to experience, no matter what mode or power or antenna you use.