Satellite operating is one of the great activities available to Ham Radio operators. With a small amount of gear and a little practice, anybody can get involved in working stations on the “birds.” It’s portable, predictable, open to all levels of license, and not dependent on good solar conditions for propagation. Like any other aspect of Amateur Radio, learning proper skills and technique can maximize your enjoyment.

Most satellites use 2 meters and 70 centimeters. You transmit (or uplink) your signal on one band and receive (or downlink) your signal on the other. When I was first starting out on sats in 2012, I had some great ops who mentored me and got me off to a good start. One of the things they kept hammering home was the need to be able to send and receive simultaneously—what is known as full-duplex operating—to have great success.

When I started working FM satellites, full-duplex seemed like an unnecessary step. After all, I had a dual-band HT and a handheld dual-band Yagi, and I thought I was reasonably successful at making contacts. But then I started noticing that I would call stations and not get through. It turns out there are a few reasons for this, and all boil down to one basic fact: You need to be able to hear when you are making it into the satellite. There are a few major obstacles that can affect your ability to make it into the birds:

- The Doppler Effect—Satellites are a moving transmitter. As they move across the sky, the frequencies they use will shift slightly, just like the train whistle that goes down in pitch as it goes past you. The tone of the whistle itself never changes, but you hear a shift in pitch as it moves past your stationary position.

Doppler shift is more pronounced the higher in frequency you go. For satellite operators, this means you will need to adjust your 70 centimeter frequency during the pass. This could be your transmit or receive frequency, depending on which satellite you are trying to hit. If it’s your transmit frequency, not adjusting for Doppler can prevent you from accessing the satellite. Both the AO91 and AO92 FM satellites use a 70 centimeter uplink.

- The Capture Effect—FM satellites are essentially orbiting repeaters, meaning only one signal will be retransmitted by the satellite. As with FM reception in general, the Capture Effect comes into play, meaning if several FM signals are present, only the strongest signal will be retransmitted. If you can’t monitor the satellite in real time, you could be passed over by a stronger signal and not realize it is happening.

- Bad Timing—With only one person able to access an FM satellite at a time, there could be several people trying at once. During passes, there are inevitably breaks or gaps in between other people transmitting. By using full-duplex during a pass, you will know when those gaps occur and can better plan your transmissions during those gaps.

Full-duplex also allows you to monitor the quality of your own signal in real time, which can help you adjust your antenna to compensate for polarity shift fading, for example.

There are plenty of people—myself included—who have made satellite contacts using half- duplex with a single dual-band HT. But there is no question that by operating full-duplex, your success rate will be higher, as will your understanding of why you might not be heard. The advantages to full-duplex on FM satellites are significant. Full-duplex can be obtained by using two separate HTs, two all-band radios such as the Yaesu FT-818, a dual-band HT capable of full-duplex operation like the Kenwood TH-D72A, or a satellite base station rig such as the ICOM IC-9700.

- Patrick Stoddard, WD9EWK, uses many different combinations of radios to work both FM and linear satellites full-duplex. This combination of a Yaesu FT-817 and an ICOM IC-R30 receiver proved very successful during his visit to the VOA Museum near Dayton during the 2019 Hamvention. [Patrick Stoddard, WD9EWK, photo]

- The author using two Yaesu 817s while roving through Montana in 2017. The front pack allows easy access to the 70 centimeter radio to adjust for the Doppler Effect while the satellite pass is occurring. [Katie Allen, WY7YL, photo]

- Popular with satellite operators, the Kenwood TH-D72A dual-band HT offers full-duplex capabilities in one radio. [Sean Kutzko, KX9X, photo]

- Ron Bondy, AD0DX, uses two HTs with a handheld dual-band Yagi to work satellites. This setup allows him to hear his own audio in real time, which lets him know his signal is making it into the satellite. [Alex Free, N7AGF, photo]

- The standard full-duplex portable satellite station: two Yaesu 817s, an Arrow dual-band Yagi, diplexer, and battery pack. This configuration is used by many satellite operators worldwide. [Sean Kutzko, KX9X, photo]

The Jump to Linear Satellites

A world of possibilities opens up when you make the jump from FM to linear satellites. Linear sats use a transponder, which provides from 20-50 kHz of bandwidth for stations to use. The modulation mode is either sideband or CW. These differences, compared to FM satellites, mean several stations can make contacts through the satellite simultaneously. Tuning through the bandwidth of a linear satellite is not unlike tuning up and down an HF band, looking for stations to make a contact with.

However, the freedom of bandwidth creates new challenges. FM satellites only have one channel to use, so there’s relatively little tuning to do. For linear satellites, you must find your transmitted signal within the passband of the transponder’s downlink. That’s also where you will find other stations calling you to make a contact; they’re hearing your signal the same way you are. Finding your own signal within a 50 kHz spread can be difficult for newer operators. This necessitates you having a second radio to find your own signal. Without knowing where your signal is landing in the downlink, you won’t hear anybody calling you who wants a contact.

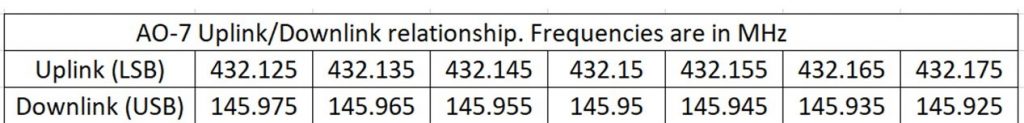

The relationship between a satellite’s uplink and downlink frequency can be computed. Most transponders are inverting. Practically speaking, this means the top end of one passband is the bottom end of the other passband. Sidebands are inverted, as well, meaning you transmit on lower sideband (LSB) and receive on upper sideband (USB).

Here’s an example: The venerable linear satellite AO-7 has a transponder with an uplink between 432.125 and 432.175 MHz. The downlink is between 145.975 and 145.925 MHz. The bottom of AO-7’s uplink passband corresponds to the top of the downlink passband. Here’s a chart that shows the relationship:

All linear satellites have an uplink/downlink frequency relationship similar to AO-7. Because this relationship is mapped out, skilled satellite operators can make contacts with only one radio, but only if they are the station calling CQ. However, it is not a recommended operating practice. Unless you are extremely skilled, the chances are you will not make any contacts at best; at worst, you could cause unintentional interference to other stations using the satellite.

More Resources

Satellite operating isn’t difficult, but having the right gear and learning proper technique will make your efforts more enjoyable. Check out my previous blogs on satellite operating basics and making QSOs via satellite. You should also review some of the getting started guides from AMSAT (The Amateur Radio Satellite Corporation). AMSAT is all about Ham Radio satellite operating. The organization has a wealth of information for newcomers, along with members who will be happy to help you get started. Here’s an example of some of the station and operating hints they have available.

Have you started operating satellites? Drop me a line if you have a question! I hope to make a contact with you on the birds soon.

Pingback: Overstappen naar lineaire satellieten - VERON