Open the box of a new handheld radio and you’ll find the usual stuff—the radio, battery, charger, belt clip, “rubber duck” antenna, and instruction manual.

Looking at rubber ducks from the outside, they appear to be much the same. Most are short, black, and have an outer rubber coating. While the exteriors are similar, the interior parts and length may be different.

Though the rubber duck antenna is often a bit of a compromise, its flexibility and durability make it ideally suited for handheld transceivers. In addition, rubber duck antennas are omnidirectional, meaning they can receive and transmit signals in all directions. This makes them useful for moving about or in a location with varying signal strengths.

But suppose you notice difficulties reaching nearby repeaters or spotty signals during public service events or ARES exercises. In that case, you might consider upgrading your factory-supplied antenna to a better one.

Change Could Be Good

In most cases, shorter loaded antennas don’t work as well as longer ones. Few are specifically tuned for the VHF/UHF ham bands. Many manufacturers (other than the big three from Japan) take a one-size-fits-all approach.

The typical frequency range for most rubber ducks of eight inches or less is 134-176 MHz, which covers a large swath of the Land Mobile Radio bands and includes VHF ham bands. Dual banders add 400-480 MHz as well.

It’s common these days to see handheld radios and their stock rubber ducks covering 2 meters and 70 centimeters, and there’s a reason. The 70cm band is close to the third harmonic of 2M. That means a single antenna for 2M can be used somewhat effectively on the 70cm band.

To make a short duck antenna act like a 19-inch quarter wave, a capacitor and/or inductor are added to the antenna. Sometimes the inductor is the antenna itself, wound in the shape of a spring. It’s known as a normal-mode helix. That keeps it in resonance with the frequency being transmitted but reduces efficiency.

The Holy Grail of rubber duck antennas is to approach the efficiency of a quarter-wave antenna while being physically shorter.

We can’t change the laws of physics, but we can have some give and take between physical length and loading. The Diamond Dual-Band SRH77CA (below) is 15 inches long—21% shorter than a 2M quarter wave—and has excellent user reviews. The Comet Dual-Band SMA-24 is about the same length and was only 1 S-unit down from the Diamond in my “unscientific” evaluation (HT on low power to base station a mile away).

Going Long

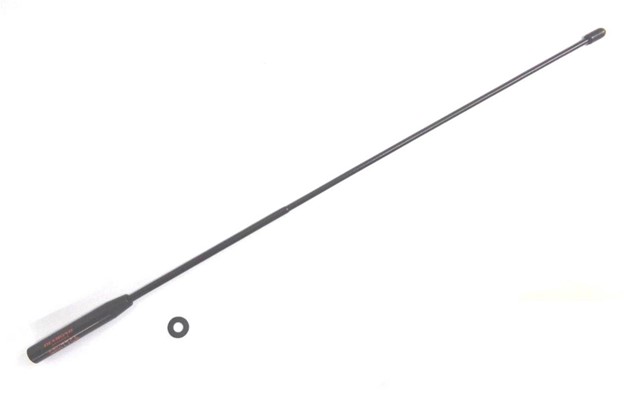

More significant improvements happen when you get an actual quarter-wave whip antenna. The 2M quarter-wave whip is longer than a factory antenna but performs dramatically better. A quarter-wave antenna tuned for the 2M amateur band is also 3/4 wave on the 70cm band. Go to a half-wave collapsible or folded tactical whip and you’ve got a built-in ground plane.

Clear communication on frequencies like 2M and 70cm depends on the line of sight between the receiver and transmitter, so the height of the antenna is also a factor in antenna effectiveness. The size of the antenna may increase effectiveness not only because of better radiation but because of better height.

The Other Half of the Story

Speaking of ground planes, HT antennas rely on the radio’s metal chassis, and you–yes, you! Hold an HT and you become the ground plane. You’re capacitively coupled to the radio and become the other half of the antenna.

You’re now di-poler.

Admittedly, you’re not an adequate ground system, and the duck is doing most of the work. To make a complete antenna, you still need a suitable ground. This can be done with the half-wave antenna mentioned earlier, or a low-cost counterpoise. All will help your radio’s efficiency.

You can easily homebrew a quarter-wave rat tail/tiger tail counterpoise by attaching any handy piece of wire about a quarter wavelength long (19.2″ for 146 MHz, 6.4″ for 442 MHz) to the radio’s antenna ground. The purpose of the rat tail is to have a handheld antenna that functions more like a vertical dipole.

This will add additional gain to both the transmit and receive performance.

Sure, it’s ugly and dangles beside your radio, but it’s a small price to pay to be heard. Construction details can be found in the OnAllBands article, “Does Your HT Have Low-T.”

***

Editor’s Note: Does the headline of this article ring any bells? If you were a fan of Weird Al Yankovic in his MTV heyday, you might have heard “I Want a New Duck,” his non-ham-related parody of “I Want a New Drug” by Huey Lewis and the News. You can listen to “I Want a New Duck” here. And to find an upgrade for your handheld transceiver’s duck, visit DXEngineering.com.